Silent Running (1972) Directed by Douglas Trumbull. Starring Bruce Dern. Screenplay by Deric Washburn, Michael Cimino, and Steven Bochco.

For just a moment, let’s time travel back to the summer of 1962. In the U.S., John F. Kennedy is president and committed to sending astronauts to the moon. Dodger Stadium is brand new. The Supreme Court issues rulings declaring mandatory prayer in schools unconstitutional and decriminalizing nude photographs of men. The Cuban Missile Crisis is lurking just a few months in the future. And, starting in June as a lead-up to a September publication, The New Yorker begins serializing a little book called Silent Spring, in which marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson documents research into the harmful effects of man-made pesticides on the natural world.

Silent Spring had a huge and immediate impact on the American public, which Carson and her publisher, Houghton Mifflin, had very much expected and prepared for. There was somewhat panicked pushback from the U.S. government and chemical industry giants like DuPont and Monsanto, but all of that only made Silent Spring more influential in public opinion. A culture of unchecked growth and technological development had dominated life in the U.S. since the end of WWII, and Carson’s book was one of the many catalysts that prompted people to seriously ask if all that progress was doing more harm than good.

The environmental movement picked up momentum over the next decade. By the end of the 1960s, the Environmental Defense Fund, founded as a direct response to Silent Spring, was actively filing lawsuits to end use of the pesticide DDT. The first Earth Day was declared in 1970; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established that same year. Environmental concerns were in the news, in the halls of government, in the courtrooms, and in the public consciousness. It’s no surprise that those themes showed up in movie theaters as well.

Humanity’s impact on the natural world—whether our own Earth or other worlds—has always been a part of science fiction, but Silent Running was not initially meant to be an environmental story at all. Douglas Trumbull had recently finished working with Stanley Kubrick, creating the special effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey, so he had big, thoughtful, serious science fiction on his mind when he first starting putting Silent Running together. His earliest conception of the film was about first contact with an alien civilization.

But it evolved, as stories tend to do, and what he ended up with is an environmental fable that simply—and not remotely subtly—calls out the dysfunction in humanity’s relationship with nature. Trumbull had never directed a film before, and in fact he would only direct one more feature in his life. (That would be Brainstorm (1983), which is largely remembered now for being Natalie Wood’s last movie, as she died during production.) What Trumbull is mostly known for is his absolutely legendary special effects work on some of Hollywood’s most influential sci fi films: 2001, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Blade Runner. So much of how we imagine science fiction to look comes from Trumbull’s special effects work.

Here are some fun details about how Silent Running was made, which I share for no real reason other than the fact that I love learning about this stuff and hope you do too:

- The exterior shots of Valley Forge and the other ships use a 25-foot model built from wood, metal, and plastic, with much of the mechanical detailing coming from literally hundreds of model kits of WWII airplanes and tanks.

- For the interior, Trumbull made a deal with the U.S. Navy to film inside the aircraft carrier USS Valley Forge, which was waiting to be decommissioned and scrapped at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard.

- The forests were filmed inside a hangar at the Van Nuys Airport, and many scenes with the stars and domes were done “in-camera,” that is, using projected footage in the live scene, rather than added afterward during processing.

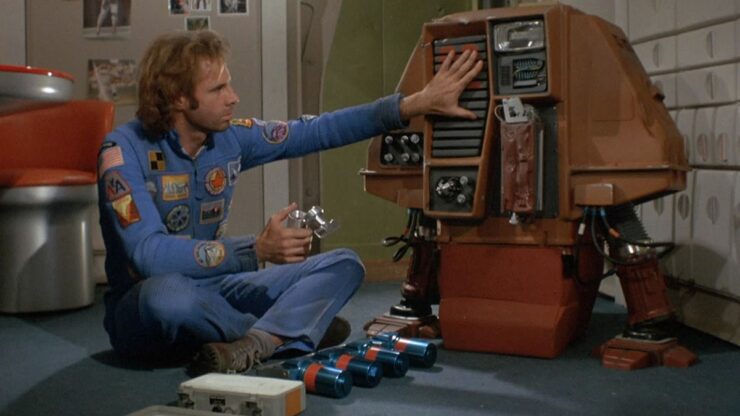

- And, finally, the three robotic drones—Huey, Dewey, and Louie—are not mechanical at all, but are actors in costume: Mark Persons, Cheryl Sparks, Steven Brown, and Larry Whisenhunt, all double amputees. (Additional fun fact: A few years later, George Lucas would direct Ralph McQuarrie to consider the Silent Running drones as an example of what he wanted R2-D2 to look like.)

On that note, if the business and craft of making sci fi movies in ’70s Hollywood interests you, I recommend Trumbull’s lengthy 1978 interview with Fantastic Films Magazine.

Trumbull was inspired by working on 2001, but he wasn’t working with 2001 money. As a result the practical effects in Silent Running are a great example of doing a lot on a comparatively limited budget, just by looking around Los Angeles and getting creative with what was available. (We are talking about more than a million dollars; this is Hollywood budgeting, not normal people budgeting.) And the film still looks really, really good. The ship exterior is visually interesting, the sense of interior space is convincing, and the images of the darkness of space outside the forest domes are hauntingly effective.

But let’s be real. The most important special effect in Silent Running is Bruce Dern’s crazy eyes.

Dern plays Freeman Lowell, a man who has spent the better part of a decade aboard the spaceship Valley Forge, caring for the last remnants of Earth’s flora and forests. The film doesn’t explain why the last pieces of nature have been enclosed in domes and launched into space aboard American Airlines spacecraft—and I have questions about what the hell American Airlines was thinking with this sponsorship, because it does not make them look good. We learn that there are no trees or plants left on Earth, no parks or wild areas, no places where kids can dig in the dirt or run through the grass. There is also, apparently, “…hardly any disease. No poverty. And everybody has a job.” Everything has been replaced by absolute uniformity: everywhere is 75 degrees Fahrenheit and everybody looks and acts the same. (Feel free to insert your own joke about Hollywood here.)

The film doesn’t dig deeply into any of this; these details emerge when the characters are arguing. I’m skeptical enough to doubt fictional characters when they claim the world has no poverty or disease, nor am I entirely convinced the audience is supposed to buy it. (The whole world? Or just the world of white guys working corporate space jobs? I have questions.) It’s vague and muddled worldbuilding anyway, so we won’t dwell on it. Whatever the intent, as a person who likes trees and seasons a lot more than I like being an anonymous cog in the grinding wheels of capitalism, I agree with Lowell that this future Earth sounds pretty bleak. But even bleaker is the fact that of the few characters we meet in the film, only Lowell believes it’s a situation than can be changed.

When Valley Forge and its fleet receive orders to destroy the precious forests and return to Earth, with no explanation except that it’s time they get on with the business of commercial shipping, Lowell is crushed, but the other members of the expedition are happy to be going home. They acknowledge that it’s kinda sad to destroy the last of Earth’s forests, but to them it’s inevitable. They don’t even question that they’re doing it just so their bosses can make more money using the ships for something else. There’s no point in trying to fight it, or dream about a different world. One of them says, “The fact is, Lowell, if people were interested, something would have been done a long time ago.”

I’ll pause there to let everybody wince before we move on.

Lowell decides to do something about it. What he decides to do is murder: he kills his three crewmates to stop them from jettisoning the last forest dome, then stages an explosion so the other ships in the fleet think he’s suffering some sort of catastrophic mechanical failure. He sets course for Saturn, hoping to run away far enough that the other ships don’t follow.

Because Lowell is the only character on screen for the majority of the film, so much of the movie depends on how Dern plays him. Contemporaneous reviews of the film had some mixed opinions about Dern’s portrayal, but I come down on the side of loving it. Even before things start to go wrong, he’s wide-eyed and strident, soft-spoken but intense, and more than a little sanctimonious. His crew uniform has a prominent Smokey the Bear patch on it, but when he’s working in the forest dome he wears a loose robe to talk to rabbits and birds, like some sort of space-age St. Francis of Assisi, complete with Joan Baez on the soundtrack. (The music was composed by Peter Schickele, better known as musical satirist P.D.Q. Bach; Diane Lampert wrote the lyrics to the songs Baez sings.) He’s a hippie, a wild man of the woods, a bedraggled mystic, a wise hermit. He’s committed to his counterculture perspective. He’s an insufferable dinner companion.

The fact that he’s right about what a terrible decision it is to destroy the forests has nothing to do with how he comes across; there is no effort here to artificially link righteousness or morality with likability. Lowell’s crewmates are good-natured and affable—they’re also the ones who laugh while blowing up cute little bunnies with nuclear bombs.

But they are Lowell’s fellow humans and almost-friends, and their deaths weigh on his conscience, even though he believes he made the right choice. The way he unravels as the film goes on is fascinating, because he uses the robotic drones to replace the crew. He reprograms them to follow his lead when it comes to work, but also to keep him company in poker games. He even has them bury the corpse of a former human crewmate, just in case the symbolism wasn’t clear enough. (About the poker: A computer scientist by the name of Nicholas Findler was programming computers to play poker in the 1970s—there may have been others, but his research articles were the ones that came up when I dug around—so this element wasn’t actually very futuristic at the time, just a few years on the early side.)

This progression grows more unsettling when Lowell teaches the drones to care for the forest, recalling the children of Earth who will never have a chance to climb a tree or play in grass. It’s interesting to me that the drones are never actually proven to have any personality or human characteristics; Lowell’s perception is what anthropomorphizes them. And when we get to the end of the film, Lowell uses the last drone to replace himself as the final caretaker of Earth’s forests. Humans may be willing to save themselves—after all, the other ship shows up to rescue Lowell, even after he assumed they would abandon him—but they can’t be trusted with the last scrap of Earth’s forests. That’s up to one little robot with a watering can.

Silent Running is far from a perfect movie. If we started listing the scientific inaccuracies we would be here all day. In a 1978 New York Times piece about science fiction, Carl Sagan wrote, “Trumbull’s characters are able to build interplanetary cities but have forgotten the inverse‐square law. I was willing to overlook the portrayal of the rings of Saturn as pastel‐colored gases, but not this.” And, really, that about sums it up. Science fiction often has very silly science.

But as a fable about man’s relationship to the natural world, the film is anything but silly. It’s heavy and melancholy, even more so now, fifty-two years of escalating climate crisis later, than it was upon release. Silent Running was a modest success at the time, sandwiched as it was in an era of some of the biggest, flashiest, most genre-defining sci fi films to come out of Hollywood, but it’s easy to see why it’s maintained a long-lasting cult status, even as its style of earnest and heavy-handed moral commentary has fallen out of style.

There are a lot of climate crisis stories in modern sci fi, but a great many of them focus, intentionally or not, on the natural world’s utility to humans: we must preserve it or else we doom ourselves. Silent Running argues that we should preserve the natural world even if we can live without it, even if it serves no purpose in feeding the hungry or curing the ill, even if we can find a way to get along just fine. That’s a less common philosophy in environmental sci fi, and it’s one of the reasons I find this film so interesting.

One last note: On the wall besides Lowell’s bunk is a copy of something called the “Conservation Pledge,” which dates back to 1946, when the magazine Outdoor Life held a contest to encourage outdoors enthusiasts to dedicate themselves to the preservation of the America’s natural resources. The winning entry, the one that adorns Lowell’s wall aboard Valley Forge, was submitted by L.L. Foreman, a former ranch hand turned author of pulpy adventure Westerns.

The second-place winner of that 1946 contest? Rachel Carson.

What are your thoughts on Silent Running and its place in the subgenre of environmental sci fi? Do the cute little drones succeed in emotionally manipulating you even when you’re fully aware you’re being emotionally manipulated? Share your thoughts below!

Next week: We’re traveling back into deep space with another (loose) adaptation of a Stanislaw Lem novel, traveling to a distant planet aboard the spaceship Ikarie XB-1. Watch it on Criterion, Cultpix (some locations), British Film Institute (UK only), and I suspect you all know how to poke around the internet for other options, if you need to. If the version you stumble across is the American dubbed release titled Voyage to the End of the Universe, take note that it has a different cut and ending.